- Home

- Christensen, Thomas

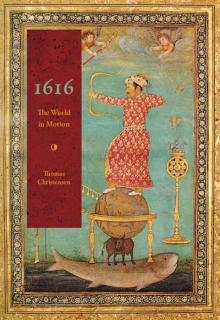

1616 Page 3

1616 Read online

Page 3

At one time China had experimented with paper currency, but that system had been abandoned centuries before. Now, in the declining years of the Ming, China’s last native dynasty, the Wanli emperor, supported by twenty thousand eunuchs and ten thousand serving women in his massive palace complex known as the Forbidden City — the largest in the world — luxuriated in the vast wealth the American silver represented. To him the king of Spain, Philip III, was known as “the King of Silver.” To maximize the value of the silk trade he had required every major farmer to devote a portion of his land to the mulberry trees that the silkworms favored. As a result, a single year’s silk trade could be worth two or three million dollars. In a good year the value of the silver that crossed the Pacific in the Manila galleons was greater than that of the entire trans-Atlantic trade.

In most years between twenty and sixty Chinese junks made the trip to Manila, but in 1616 only seven junks arrived. From Manila one to four galleons would make the hellish eastward passage to Acapulco each year. The massive ships would set sail around midsummer and usually arrive in Acapulco in January or February. An Italian traveler who made the trip later in the century reported that “the Voyage from the Philippine Islands to America, may be call’d the longest and most dreadful of any in the World.” But both of the galleons departing from Manila in 1616 would be forced to return to port.

For more than half a century Spain had dominated much of the Pacific, which had come to be known as “the Spanish Lake.” What was the cause of the failure of the Pacific trade in 1616? It may have been attributable in part to a new presence in the Pacific, one that threatened the very existence of the Spanish colony in the Philippines and the foundations of the Spanish empire.

Even as James and his court watched and participated in their extravagant masque, a ship under the Dutch captain Willem Schouten was approaching the southern tip of South America. There Schouten would discover a new passage to the Pacific through chilly waters overlooked by a promontory he would name Kaap Hoorn, after his birthplace in the Netherlands; the English, betrayed by the false cognate Hoorn, would call this Cape Horn. It was not an easy passage: a tradition would develop that any sailor who had made it across earned special privileges, such as the right to wear a gold loop earring and to dine with one foot on the table. Meanwhile, other Dutch vessels under Joris van Spilbergen, having navigated the narrow Straits of Magellan, had already made their way up the Pacific coast of the Americas, plundering and terrorizing the Spanish along the way.

Portrait of a Civil Official, early seventeenth century. China. Ink and colors on silk, 89 × 157 cm (image). Asian Art Museum, 2007.25.

Over the long span of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), China’s meritocracy, built on command of the Confucian classics as demonstrated in examinations, produced a large bureaucracy in which civil officials were often at odds with the emperor and the eunuchs of the Forbidden City. Resulting governmental inefficiencies contributed to the weakening of the state, which in 1644 would give way to the Manchurians of the Qing dynasty.

Suddenly the Pacific was a stage of battle between the Chinese, Japanese, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and English, along with various local kingdoms. The conflicts spilled over into South and West Asia, where the Turks, Persians, and Mughal Indians vied for supremacy. With the rounding of Cape Horn and the new global economy based on American silver, globalism had become a reality.

Van Spilbergen was in the service of a powerful entity that was challenging the preeminence of Spain. This was a new kind of power that would soon make the Habsburg empire of loosely confederated monarchies seem positively quaint. Van Spilbergen had been charged with sailing across the Pacific to Java, an important source of spices (nutmeg was more valuable than gold at this time), by the Dutch East India Company — the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC. The States-General of the Netherlands had granted the VOC a monopoly on trade in Asia. Even though Spain and the Netherlands had made uneasy peace in 1603, the VOC retained for itself the right to wage war if it saw the need to do so — in distant locations agreements made back home were not always observed. It could also coin its own money, establish colonies, and make treaties with other powers. The company had issued stock to international investors to whom it would pay dividends. Rather than finance expeditions on a one-off basis as had been the mode until now, the VOC was looking for long-range profit from a coordinated series of ventures. The English East India Company was formed around the same time along similar lines. These new powers were, in short, the world’s first megacorporations.

Warfare was pervasive. In the Americas, constant warfare together with epidemic diseases had over the past century reduced the native population to less than 10 percent of pre-contact numbers. Europe was on the brink of the prolonged and devastating conflagration known at the Thirty Years War. It would be the most traumatic European war prior to World War I. Japan, on the other hand, exhausted from its own internal battles, was entering a new era of uneasy peace. Korea, scarred and recoiling from two brutal invasions by the Japanese, was also retreating into isolationism.

The third East Asian power, China, which had sent large numbers of troops to defend Korea, was also tired. The Wanli emperor had reached an impasse with the civil bureaucrats of his regime, who objected to his personal excesses. In effect, both sides had a sort of veto power over much of the workings of the government, with no mechanism for resolving disagreements. As a result the corpulent emperor had withdrawn inside his inner palace, and the government was effectively paralyzed. China was widely seen as rich but weak, and Mongols, Japanese, and Spaniards were among those watching for an opportunity to go in for the kill. Even the Manchu vassals to China’s northeast mocked its claim to be the center of the world to which all other states must pay tribute. In 1616 a Manchu leader named Nurhaci — who had observed that Chinese generals sent to check him usually just made a few meaningless maneuvers and then falsified their reports — would have the audacity to proclaim himself the head of a new dynasty.

In Southeast Asia all the world’s major powers were engaged in a messy fight for supremacy in trade profiteering. Portugal, once the principal European power in the region, was struggling to maintain its bases in Goa and Melaka. Spain knew that it had to confront the Dutch and English, but the defeat of its armada in the English Channel in 1588 and subsequent military setbacks in the Netherlands, on its border with France, and in its own principality of Naples had undone the optimism of the allied European defeat of the Ottomans at Lepanto and the surprising successes of Spain’s outmanned conquistadors in the Americas. Now, in Manila, it was assembling a new armada that would be by far the greatest naval force ever seen in those waters, and it hoped this time to have greater success.

Around the Indian Ocean the Portuguese had been a commanding presence throughout the sixteenth century, but now their dominance was declining. Even at its height it was never as great as Western historians used to suggest — power shifts in the region had been as much the result of the rise of the three great Islamic empires, the Ottomans of Turkey, the Safavids of Persia, and the Mughals of India, as they had been of the entry of the Portuguese into the region. Having rounded Africa, the Portuguese had fastened onto existing networks of trade and exchange. They had mostly been content to establish a chain of fortified coastal cities to support their maritime activities. But now the Dutch and the English had begun penetrating into the interior of many parts of Asia.

The Dutch and English competed in Asia not just with preestablished powers but also with each other. In 1616 they did battle over the tiny island of Run in the Moluccas archipelago, which was rich in nutmeg, a single sack of which could set a man up for life. The Dutch were led by the ruthless Jan Pieterszoon Coen, whose motto was “Spare your enemies not, for God is with us.” True to his word, he would later massacre virtually the entire population of the Banda Islands, in one of history’s most notorious incidents of genicide. Ultimately the English lost the Spice Islands of Southeast Asi

a to the Dutch, and they were forced to concentrate their activites farther north. (The two powers later signed a treaty by which England conceded its claim to the Spice Islands, receiving. Manhattan in exchange. It seemed to the Dutch a good deal at the time.) In 1616 England sent its first official ambassador to the Mughal court of Jahangir.

The three Islamic powers derived the authority and legitimacy for their regimes in different ways. The Ottomans, who had little genuine claim to dynastic rule, derived their prestige from military might; they asserted no religious authority except through their role as warriors for Islam. The Mughals carried the prestige of an illustrious dynastic pedigree. Religious figures had influence but little aspiration to political power in Mughal India (where the majority subject population was Hindu), but in Safavid Persia, where authority depended on religious righteousness, they went so far as to claim that even political power should reside in the religious leadership — an aspiration finally realized centuries later, in 1979. All three powers were engaged in territorial battles. Mughal leaders sought to consolidate and expand their territories south through India while holding ground against Safavid Persia in current Pakistan and Afghanistan. The success of Shah Abbas in overcoming Persian factionalism allowed him to check the expansionist ambitions of the Ottomans, who were unable to fully pursue their long-standing battle with Christian Europe because of the Persian threat from the east and the encroachments of cossacks from the Russian steppes to the north. Pressured on all fronts, and damaged economically by the influx of American silver into Europe, the Ottomans would eventually be forced to abandon their goal of expanding farther into Europe.

Shah Abbas I and a Pageboy, 1627, by Muhammad Qasim. Isfahan, Iran. Ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper. Louvre, Paris.

Shah Abbas I “The Great” made Safavid Persia an important player on the world stage. Under his rule Persia became a significant check on the power of the Ottoman empire. Abbas also established diplomatic relations with European powers, and several European travelers visited him at his court in Isfahan, which he made his capital in 1598.

It has been suggested that this scene depicts a New Year’s feast. In Persia the new year began on March 21. The inscription reads “May life bring you all you desire of three lips: the lip of your lover, the lip of the stream, and the lip of the cup.”

This is one of the last portraits of Abbas, who is recognizable by his distinctive drooping moustache. The artist, Muhammad Qasim, shows an awareness of both European and Chinese painting styles, reflecting both Persia’s strategic geographic position and the effects of nascent globalization in the early seventeenth century.

Suffering through what is known as its Time of Troubles, Russia seemed hopelessly ensnared in conflict. After the deaths of Ivan the Terrible and his successor Boris Gudonov, the country was desperately searching for a new leader. But only impostors appeared to claim the throne, and legitimate heirs ran away when they heard the call to assume the role of tsar. Finally, kicking and screaming, a young man named Mikhail I Fyodorovich Romanov had been hauled to the throne, and the long rule of the Romanovs had tottered off on its iffy beginnings, as the nearly leaderless country was locked in seemingly hopeless battle against the formidable powers of Sweden and Poland.

Even the Jesuits had turned militaristic. In South America they had formed what they called “reductions.” These were utopian societies of native peoples whom the priests armed and trained as military forces to repel bandeirantes — slavers and fortune-hunters — from Brazil. In 1616 nearly three hundred Belgian Jesuits would travel to the Rio Plate to join the heavily armed, cultlike, millenarian communities.

But attitudes toward warfare were slowly changing. In the West, members of the aristocracy had traditionally been defined by their prowess as warriors, and in paintings they had nearly always been depicted in martial poses. Now a courtier like Buckingham could advance through prowess not on the battlefield but on the dance floor, and the elite were as likely to be painted as scholars surrounded by books as they were to be depicted as military leaders. In Japan military prowess was giving way to ritual symbolism, and samurai armor, designed for ceremonies, would eventually become so stylized as to be impractical for battle. In 1616 the Dutch painter Rubens was still doing martial studies of young men in armor, but within a few years he would turn from celebrating warfare to depicting its atrocities and devastations; a similar change would occur later in the century in the paintings of Spanish artists such as Diego Velázquez.

In China some of the educated elite, disgusted with the excesses and corruption of the imperial court, withdrew from it entirely. They retreated to country cottages to write poems or paint landscapes. One writer, calling himself “the Scoffing Scholar of Lanling,” devoted years to constructing an elaborate erotic novel that reached a length of 2,923 woodblock-printed pages.

Significant changes were being seen in social roles. While witchcraft, formerly gender-neutral, had increasingly come to be associated with women, in other areas women were beginning to break into once exclusively male domains. In Florence the artist Artemisia Gentileschi would be accepted this year into the academy of painters, the first woman so honored. This was a remarkable triumph, as only a few years before she had fled to Florence from Rome, where she had been the focus of a scandalous and humiliating trial. She had been raped by an associate of her father. To test her truthfulness the authorities had invasively examined and cruelly tortured her.

This was also the year the Powhatan maiden Matoaka — also known as Rebecca Rolfe but best known as Pocahontas — would travel to England, where she would witness a court masque entitled The Vision of Delight, featuring Buckingham, the king’s new favorite. Although most of the world’s population spent their lives within about twenty miles of their homes, there were many remarkable travelers like Matoaka, several of whom have left accounts of foreign wonders. In addition to adventurers and fortune-seekers, especially from England, Spain, Portugal, Italy, the Netherlands, China, and Japan, there were traveling peddlers and merchants — Malay merchants were helping to spread Islam throughout Southeast Asia — and there were also traveling diplomats, refugees, slaves, explorers, pilgrims, artesans, missionaries, and even a few tourists, traveling not in any of those capacities but for personal gratification. A wandering Scot named William Lithgow traversed Europe and crossed North Africa, dining along the way with the corsair Yusuf Reis in his palace in Tangiers. Lithgow’s countryman the scholar and linguist George Strahan traveled to Isfahan in Persia and conversed with Shah Abbas. Another European traveler in West Asia was an Italian named Pietro Della Valle, who carved his name on a pyramid in Egypt and got a souvenir tattoo on a visit to the holy land. In 1616 della Valle joined a caravan to Baghdad, where he married a woman who had grown up there, in the heart of the Ottoman empire; together they would continue on to Isfahan, the new capital recently constructed by the Persian shah, and from there head on to India.

Susanna and the Elders, 1610, by Artemisia Gentileschi. Oil on canvas, 121 × 170 cm. Schloss Weissenstein, Pommersfelden, Germany.

Susanna and the Elders is the first dated and signed work by Artemisia Gentileschi; it was painted when she was seventeen years old, prior to the rape and notorious trial that resulted in her moving to Florence, where she became a member of the academy of painters in 1616.

In the biblical story, Susanna is a virtuous women who was sexually harassed by the elders of her community. Male artists of the Italian Renaissance had typically depicted Susanna as flirtatious, but Gentileschi depicts her recoiling from the menacing elders’ attentions.

Gentileschi was raped by a painter named Agostino Tassi, a colleague of her father. In 1616 Tassi was painting frescos in the Quirinale Palace in Rome that depicted ambassadors to the Vatican from Persia, Japan, and elsewhere (pp. 252, 335). It is possible that unwelcome male attentions contributed to Gentileschi’s unusual interpretation of the traditional scene.

One of the most curious travelers was an

ambitious author on the fringes of Ben Jonson’s circle named Thomas Coryate. He had made a literary splash with an account of his travels through Europe — almost all on foot, in a single pair of shoes (which he subsequently displayed in his hometown church, where they continued to hang until the nineteenth century). The book was entitled Coryat’s Crudities: Hastily Gobbled up in Five Months Travels in France, Italy, Rhetia Commonly called the Grisons Country, Helvetia Alias Switzerland, Some Parts of High Germany and the Netherlands; Newly Digested in the Hungry Aire of Odcombe in the County of Somerset, and Now Dispersed to the Nourishment of the Travelling Members of this Kingdome; it had become a literary sensation. Eager to outdo that best-seller, Coryate decided to extend his range, and from Turkey he hiked to India, where he addressed Jahangir; 1616 found him in India, concerned that he had bitten off more than he could chew and despairing of ever returning to publish his new volume.

Greeting from the Court of the Great Mogul, 1616. Cover of a book by Thomas Coryate. London.

Thomas Coryate described his European travels in 1611 in a hefty but entertaining travelogue entitled Coryat’s Crudities, which became a best-seller.

Five years later, determined to outdo that success, he set out on new travels through the eastern Mediterranean and West Asia, ending up in 1616 in India, where he addressed the Mughal emperor Jahangir. A collection of his letters from India was collected in this small book published in London in 1616.

Another notable traveler was a samurai named Yamada Nagamasa. Japan was one of the most active powers in East and Southeast Asia in the early years of the seventeenth century. Some of the vessels that departed almost every day from its harbors were known as “red seal ships.” These were combination merchant ships and warships — in this respect rather like those of the Dutch VOC — and they traded actively in the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, and elsewhere. Traveling on these ships, some Japanese founded colonies in such far-away places as Vietnam and Thailand. Yamada Nagamasa, a Zen practitioner who became a samurai warrior and was said to have proved his mettle by quelling ghosts and witches in his native Japan, journeyed in one of the red seal ships to Thailand. There, thanks to his skill as a warrior and the superiority of Japanese swords, which were the finest in the world, he played a role in installing a new king on the throne of Ayutthaya, as the kingdom of Thailand was then known. For years he ruled as the governor of a province in southern Thailand.

1616

1616