- Home

- Christensen, Thomas

1616 Page 2

1616 Read online

Page 2

Now, even as the murmuring audience in Whitehall was called to attention by the “lowd musick” that announced the beginning of the masque and watched the goddess Pallas Athena (a role once played by the queen herself) descend from the heavens on her chariot, Somerset languished in prison awaiting his trial. Meanwhile, the king had found a new favorite in George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, who was famous for his shapely legs.

The theme of the masque, the reform of a corrupt court, was well chosen by Jonson to play against the Somerset scandal, which was still on everyone’s tongue. The masque presented James, by analogy to the supreme Roman deity Jove, as a reforming king who was clearing his court of evil influences. This conceit so pleased James that he would call for a second performance five days later and present Jonson with an annual pension of a thousand marks. This would largely free the forty-three-year-old author from the need to earn his living, and though he would continue writing masques, he would not pen another play for a decade.

In his marital relations, James did not benefit from the example of his parents. As a young widow his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had chosen for her second husband her cousin Henry Stuart. After an initial moment of ardor, the two royals discovered that they detested each other. Henry became suspicious of Mary’s Italian secretary (who was rumored, almost certainly falsely, to be James’s real father), and he fell in with a group of plotters who were embroiled in palace intrigues, goaded on by anti-papist hysteria. The schemers contrived to murder the secretary, with Mary forced to witness the brutality. Pregnant with James at the time, Mary felt, not unreasonably, that she and her unborn son would be the next targets, as that would clear the way for Henry to rule. But she wisely disguised her fury, and not long afterward Henry was found inside a building that had exploded around him (the same thing nearly happened to James in the Guy Fawkes Gunpowder Plot of 1605).

George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham, attributed to William Larkin, ca. 1616. Oil on canvas, 119 × 206 cm. National Portrait Gallery; Given by Benjamin Seymour Guinness, 1952, NPG 3840.

The Duke of Buckingham, the favorite of King James I of England, was famous for his shapely legs, which he displayed on the dance floor in court masques and other festivities.

By 1616 painters had largely abandoned the martial poses and military regalia in which courtiers had traditionally been portrayed. In the new world order of the early seventeenth century nobility was adorned instead with the trappings of culture.

It is hard to imagine anyone going to battle in the shoes Buckingham is wearing in this portrait.

Then it was discovered that it was not the explosion that killed Henry — he had been strangled prior to the blast. Mary, who had imprudently married Henry’s chief enemy, was imprisoned and forced to abdicate. She escaped and fled Scotland for London, never to see her son again. In London she remained under the watchful custody of Elizabeth for nearly twenty years, until she became implicated in far-fetched plots against her cousin’s throne. When Elizabeth ordered her execution, James, now king of Scotland, turned a cold face, seemingly little moved by his mother’s plight.

It was a dangerous time to have close blood ties to a reigning monarch. Although many royals eased into lives of privilege, palace intrigues could often turn injurious or deadly, as had been the case with several of the world’s current rulers. Louis XIII of France (who was branded by his prime minister, Richelieu, as “Louis the Just” to avoid his being known as “Louis the Stammerer”), having assassinated his mother’s favorite, the regent, then led an army against her. Shah Abbas, who made Safavid Persia a player on the international stage, had his first son murdered, and his second and third sons blinded. In India the Mughal emperor Jahangir, a great patron of the arts, likewise had a son blinded to prevent him from challenging the throne. The stepmother and half brother of the Japanese shogun Tokugawa Hidetada were both killed by his father, Ieyasu, the first shogun of the long Tokugawa (Edo) era, on suspicion of plotting against him. Mehmed III, sultan of the Ottoman empire from 1595 to 1603, had all nineteen of his brothers killed.

In The Golden Age Restored, Jove, the king of heaven, oversees the action, just as James, the king of England, was overseeing the masque. Now Pallas Athena, having alighted, announces that Golden Age and Astraea, goddess of justice, are to be restored to earth. But this plan is temporarily thwarted by Iron Age and his twelve attendant evils — Avarice, Fraud, Slander, Corruption, Ambition, Pride, Scorn, Force, Rapine, Treachery, Folly, and Ignorance — who threaten to disrupt the order of Jove’s dominions “and teach them all our Pyrrhick dance.” Finally Pallas puts them to flight and Golden Age and Astraea descend in the company of four English poets laureate. They introduce the masquers, who dance about the hall to the delight of all.

A desire to replace the fragmentation of the medieval world with something resembling the far-reaching cultural and political cohesion of ancient Rome was an impetus for the European Renaissance, as first voiced by writers such as Petrarch in the fourteenth century; the Golden Age of the masque is a lingering expression of that ideal. Fueled by the ancients’ example of greatness (and by the movable metal type printing press, an East Asian invention reverse engineered in Germany), Europeans reconfigured their society in a remarkably short time. During the age of Shakespeare it had seemed that anything was possible, and that the whole chain of being could be encompassed within a single vision. But now cracks were appearing in the old unities. Some Europeans were questioning the applicability of the ancient models — “’Tis all in pieces,” John Donne had written five years earlier, “all coherence gone” — and the European world was teetering on a pivot that could propel it in different directions.

Throughout the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century, Western scholars, mindful of European success in colonizing other areas, viewed Europe as historically exceptional, developing in radically different ways from other regions. The West was seen as more dynamic, rational, and democratic than any part of Asia, which was portrayed as monolithic and static, unchanging across centuries. But in fact the early seventeenth century was a time of enormous change in most regions of the world, change largely driven by a new maritime globalism that accelerated trade and exchange of goods and ideas. In the face of such unsettling changes, many cultures looked back nostalgically to earlier times as “golden ages,” and these eras served also as models legitimizing emerging states that were consolidating regions once made up of numerous small, independent principalities. In Europe five or six hundred political units would eventually merge into just a couple of dozen; in mainland Southeast Asia a couple of dozen states would resolve into just a handful; and so on. Contributing to this consolidation was the new availability of firearms and cannonry, which compounded the political advantages of centers of wealth. While Renaissance Europe looked back to ancient Rome, Ming China looked back to the pre-Mongol Song dynasty as a golden age, Tokugawa Japan to the pre–civil war Kawakura and Muromachi periods, Romanov Muscovy to early Orthodox Christian Kiev Rus, Burma to Pagan, Siam to Angkor, and the Vietnamese states to Confucian Dai Viet. The three Muslim empires, the Anatolia-based Ottomans, the Persia-based Safavids, and the South Asia–based Mughals, though each possessing Turkic lineage, all respected Persian culture and looked to the Perso-Islamic reign of the fifteenth-century Timurid ruler Sultan Husain Baiqara of Herat as a golden age of art and literature. Throughout the world, artists, writers, and political leaders were now struggling between evolving new forms and respecting the models of the glorious past.

Though it was an age of colorful figures and flamboyant gestures, with the growth of the modern state also came the beginnings of the state as a faceless bureaucracy. Shah Abbas of Persia, one of the age’s most extravagant rulers, remarked that “the king of Spain and other Christians do not get any pleasure out of ruling.” While the image of Abbas as a capricious despot making life-and-death decisions on a whim owes much to the Western orientalizing impulse, there is substance to his criticism. A memb

er of the court of the Spanish king, Philip III, commented that “no secretary in the world uses more paper than His Majesty.” Philip passed his days reviewing document after document — he once signed four hundred documents in a single day; by contrast, his grandfather, Charles V, had once called for a pen and found that there was not a single one to be located in the entire palace. But it was not just in Europe that some courts had become stultifying bureaucracies. The same charge could be leveled at the Ottoman court under Abbas’s colorless counterpart Ahmed I, while in China the Wanli emperor spent his days engaged in mechanical rituals and endless paperwork.

Inigo Jones’s designs for The Golden Age Restored have not survived, and we don’t know exactly how the masque was produced. In general, masques were elaborate and expensive affairs. For 1608’s The Masque of Beauty, another Jonson and Jones collaboration, we know that the ladies were opulently adorned with pearls and jewels, and an Italian observer claimed a single outfit could cost better than 100,000 pounds. Records of the king’s keeper of accounts detail payments of nearly 6,000 pounds on such items as gold and silver lace, gold chains, silks, linens, and other luxury items. Although it is hard to establish equivalents, in modern currency this might approach half a million dollars for the evening’s entertainment.

Courtiers too were expected to live large and spend lavishly. Lord Hay, a gentleman of the king’s bedchamber, commissioned a masque entitled Lovers Made Men for a private reception in honor of an ambassador from France. For the occasion he spent more than 2,200 pounds on the dinner alone, employing thirty chefs over the course of twelve days. Finally, on the occasion of the feast, a splendid meal was placed on the table and uncovered … and cleared away before a bite was taken. This gesture was intended only to stimulate the guests’ appetites, and a second, even more magnificent meal was then set before them.

A reception in 1606 for the queen’s brother, Christian IV of Denmark, was said by an observer to have devolved into a sloppy, drunken spectacle:

In good sooth the parliament did kindly to provide his Majestie so seasonably with money, for there hath been no lack of good livinge; shews, sights, and banquetings, from morn to eve…. One day, a great feast was held, and, after dinner, the representation of Solomon his Temple and the coming of the Queen of Sheba was made, or (as I may better say) was meant to have been made, before their Majesties, by device of the Earl of Salisbury and others…. The Lady who did play the Queen’s part, did carry most precious gifts to both their Majesties; but, forgetting the steppes arising to the canopy, overset her caskets into his Danish Majesties lap, and fell at his feet, tho I rather think it was in his face…. Now did enter, in rich dress, Hope, Faith, and Charity: Hope did assay to speak, but wine rendered her endeavours so feeble that she withdrew, and hoped the King would excuse her brevity: Faith was then all alone, for I am certain she was not joyned with good works, and left the court in a staggering condition…. Hope and Faith … were both sick and spewing in the lower hall. Next came Victory, in bright armour, and presented a rich sword to the King … after much lamentable utterance, she was led away like a silly captive, and laid to sleep in the outer steps of the ante-chamber.

The result of all this was that by 1616 the English monarchy was in dire financial straits, and The Golden Age was probably scaled back from the earlier level of excess. Records related to the masque of 1612 show an outlay of only 280 pounds, although by 1617 the price had again risen to 2,000 pounds. Having squeezed about as much in “loans” from his subjects as he could manage, James would now turn in desperation to the aging adventurer Sir Walter Raleigh, whom he had kept locked inside the Tower of London for the past thirteen years on suspicion of treason. Raleigh would be released at last to search for the gold mines of El Dorado, which he claimed to have discovered in Venezuela during his 1594 voyage to America. But the new expedition would be likely to bring him into conflict with the Spanish, a prospect that made the English king extremely nervous.

For the previous hundred years Spain had been the preeminent Western power. Its might would soon be exposed as something of an illusion, since it rested on the foundation of an unsound and antiquated economy at home. But it was kept churning through vast amounts of gold and silver from Mexico and above all by silver from the rich mines of Potosí in present-day Bolivia. Mexico and South America at this time produced 80 percent of the world’s silver and 70 percent of its gold. In Spanish there is an expression that is still used today: Vale un Potosí. It’s worth a Potosí. It’s worth a fortune. To extract the silver from the mines the Spanish used first native labor and then slaves imported from Africa.

Slavery was common in many parts of the world. Miguel de Cervantes, author of the Quixote — like Shakespeare, now in the final months of his life — had once been captured by North African corsairs (state-sponsored pirates) and forced to labor as a slave for five years. Corsairs in the service of the Ottomans were the most feared power in the Mediterranean. The most prominent of these was Yusuf Reis — or Jack Ward, as the onetime common sailor from Kent had been known before he converted to Islam. Now he had grown wealthy and lived lavishly, attended by Christian slaves captured in the waters of the Mediterranean by his swift raiding ships, in a majestic palace in Tangiers. A popular ballad portrayed him taunting King James:

Go tell the King of England, go tell him this from me,

If he reign king of all the land, I will reign king at sea.

Slaves were often treated cruelly, but traditionally they had been regarded as people rather than subhuman commodities. Some slaves rose to positions of power. Malik Ambar, an Ethiopian slave who was traded several times, ended up in India, where he became prime minister of a sultanate in the Deccan region. There, as a pioneer of guerilla warfare, he was currently a thorn in the side of the mighty Mughal ruler Jahangir. But the American slave trade that was now being developed by Portugal — the first African slave would be brought to the Bahamas this year — was different in nature. These slavers subjected their captives to horrific and degrading conditions that surpassed anything previously seen.

In the Potosí silver mines of the Bolivian Andes conditions were harsh, and the life-expectancy of the miners was no more than a handful of years. Many died of poisoning from the mercury that was used to separate the silver. In the early months of 1616 a native of the Andes named Guaman Poma — his name means Falcon Puma in the Quechua language, and he claimed to be descended from Inca royalty — completed his monumental The First New Chronicle and Good Government, which detailed the abuses of the Spaniards. He had worked obsessively on the book for years and now was anxious to send it to Philip III of Spain in order to instigate reforms. But there is no evidence that the Spanish king ever saw the book, and it ended up in a royal library in Denmark, where it was not rediscovered until a German researcher happened upon it in the twentieth century.

Much of the Potosí silver was sent to Mexico, where it was made into Spanish dollars. The dollars were worth eight times another unit of Spanish currency, the real (a Spanish word meaning “royal”). Because of this, the Spanish dollars were known to English speakers as “pieces of eight,” and they were the basic unit of the seventeenth-century global economy. Nearly two hundred years later, when the United States would come into existence, it would match its dollar to this one. Until the summer of 1997, equities on the U.S. stock exchange were priced in ⅛-dollar increments as a legacy of the pieces of eight.

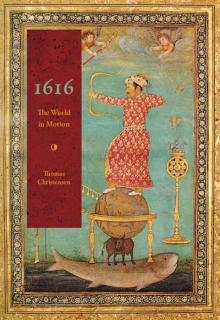

The Mughal Emperor Jahangir Shoots an Arrow through the Mouth of the Decapitated Head of Malik Ambar, 1616, by Abul Hasan. Opaque watercolors on paper, 27 × 39 cm. Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, CBL IN 07A.15.

The former African slave Malik Ambar rose to the position of prime minister of a state in the central Indian plateau, where he led resistance against Mughal expansion. The Mughal emperor Jahangir never managed to kill Malik Am-bar, but this dreamlike painting expresses his wish to do so.

In the painting Jahangir, whose name means “seizer of the world,” stands on

a globe, which shows India at the center. On the stand at right are emblems of Mughal ancestors going back to Tamerlane. The fish and ox at the bottom of the painting convey that Jahangir’s dominion extends over land and sea. Though the Mughal court was Muslim, the fish is a symbol drawn from a Hindu creation myth, while the angels at top are of Christian origin and reflect the presence of Portuguese, centered nearby in Goa on the Indian Ocean coast.

Apart from precious metals, the most coveted commodity on the international market in 1616 was silk, either raw or in the form of sumptuous textiles, and the most important producer of these was China. In The Golden Age Restored the goddess Pallas Athena sings the praises of the new golden age:

Then earth unplough’d shall yield her crop,

Pure honey from the oak shall drop,

The fountain shall run milk:

The thistle shall the lilly bear,

And every bramble roses wear,

And every worm make silk.

Chinese silks, along with other goods, were brought to Manila in the Philippines on large sea-going junks that carried 200–400 men each. There the silks would be traded for the silver of the Americas, now in the form of Spanish dollars. Those dollars served as the basic currency of China.

Punishments of Miners, by Guaman Poma, drawing 325 from El Primer Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno (“The First New Chronicle and Good Government”), 1615–1616, by Guaman Poma. Bound book; ink and colors on paper, 119 × 205 cm. Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen, Denmark.

The native Andean writer Guaman Poma completed his massive The First New Chronicle and Good Government in 1616 with the goal of persuading King Philip III of Spain to institute reforms to curtail abuses of native people in Peru (which at the time included modern Bolivia, where the silver mines of Potosí were located).

1616

1616