- Home

- Christensen, Thomas

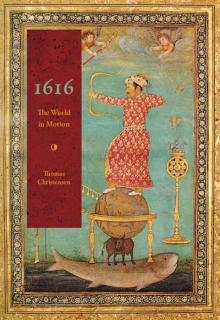

1616 Page 4

1616 Read online

Page 4

He was not the only samurai to travel great distances. In November 1616 Pope Paul V welcomed a samurai named Hasekura Tsunenaga to St. Paul’s in the Vatican. Hasekura’s embassy was unprecedented. He had crossed the Pacific to Acapulco and traveled by donkey across New Spain to Veracruz on the Caribbean coast. From there he had sailed to Seville in Spain on his way to Rome; on the return he would pass by way of Manila. His arduous journey was intended to secure trade agreements between Japan and the European powers.

But over the years Hasekura had been away Shogun Hidetada had grown alarmed by inroads made into Japan by evangelical Europeans, and he had decided to outlaw Christianity and slam the door on all outsiders. Once the missionaries gain a foothold, can the soldiers be far behind? Over the course of the current year he would increasingly impose restrictions and penalties on foreign contact, finally almost entirely closing Japan off to the outside world, a closure that the country would sustain for two and a half centuries — Japan’s next embassy to Europe would not occur until 1862.

Harlequin, early seventeenth century. Murano (Veneto), Italy. Glassware. Castel Vecchio Museum, Trent, Italy.

Murano glass workers were among the best in the world. Their expertise contributed to the refinement of the telescope by Galileo.

Harlequin began as an acrobatic comic servant in the Commedia dell’Arte. His original patchwork costume was already starting to assume its later more regular diamond pattern in this piece of glassware.

Japan had largely withdrawn, but there were still plenty of masquers on the international stage to take part in 1616’s “pyrrhic dance.” In London’s Whitehall, Astraea, the goddess of justice, appeared to have the final word. As the masque drew to a close, she predicted the advent of a new world order:

It is become a heaven on earth,

And Jove is present here,

I feel the God-head: nor will doubt

But he can fill the place throughout,

Whose power is every where.

This, this, and only such as this,

The bright Astræa’s region is,

Where she would pray to live,

And in the midst of so much gold,

Unbought with grace or fear unsold,

The law to mortals give.

Forging a heaven on earth is a tall order. Would Astraea really have the final word? How would the masque’s aristocratic fantasia compare to the reality of the year 1616? Would the golden age be restored? Were the revelers the vanguard of a new world order? Or were they just lost in a masquerade?

Acapulco Bay (detail), color lithograph from a 1628 watercolor probably by Johannes Vingboons based on a drawing by Adrian Boot. Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

Adrian Boot designed and oversaw the construction of the Castilo San Diego in 1616 to protect the only authorized American port for the lucrative Asian galleon trade. In this lithograph based on a drawing by Boot himself and bearing his signature, the five-sided fort can be seen on its promontory overlooking the bay, below and to the right of the figure arriving on horseback by way of the China Road from Mexico City. Below the fort lies the sparse settlement of the town itself, and the drawing shows the advantageous situation of the bay as a harbor for vessels.

For the complicated provenance of this image and those of Mexico City and Veracruz on pages 39 and 81, see the Source Notes section, p. 362.

1Silk and Silver

The China Road was not much of a road. Little more than a furrow spattered with mule droppings, it wound for more than two hundred miles from the capital on its high plateau through rugged mountains, dense Brazilwood forests, and desolate plains before giving itself up onto the broad, deep bay. The trip usually took about a week to ten days and required several river crossings. Constructed by native laborers and first opened to pack animal travel in 1573, the road was not made passable for wheeled vehicles until 1927. Around the bay spread a village of barely a thousand souls — Filipinos, Malays, Chinese, mestizos, runaway slaves — who lived out a hand-to-mouth existence in rude shacks. Mixed in with the dwellings was a handful of public buildings: a church, a convent, a hospital, a treasury office. With its punishing heat, pestilent marshes, venomous snakes, relentless insects, and scarcity of fresh water, the town was unfondly known as “the door to hell.”

High granite walls encircled the arc of the bay, plunging down to the sea, except for the thin strip on which the town rested. They reflected and amplified the tropical light, flooding it onto the town. The mountain walls extinguished any hope of cooling sea breezes (in the eighteenth century an opening was cut through them to bring some relief), but the sheer slopes also made the bay extraordinarily deep, right up to the shelf of the sunbaked shore. As a result, large ocean-going vessels could come so close that the seamen would sometimes just tie up to a tree rather than anchor farther out in the bay. The bay’s semicircular shape, together with an island that divided it into two parts, created an inner harbor that sheltered ships from sea winds. One world traveler who passed through in the 1600s rated it “the best and safest harbor in the world.”

It had a reputation as an unhealthful place, a reputation that didn’t improve over time. In the sixteenth century Spanish bureaucrats stationed there called it “a hot and sickly land” and begged to be “freed from the captivity” of their posts. In the seventeenth century an Italian traveler dismissed it as “mean and wretched,” littered with houses “made of nothing but wood, mud, and straw.” In the eighteenth century a governor of the Philippines described it as “an abbreviated inferno” full of “venomous serpents,” while a French navy captain called it “a miserable little place, though dignified with the name of a city; and being surrounded with volcanic mountains its atmosphere is constantly thick and unwholesome.” In the nineteenth century another French visitor complained of the “frightful” climate and judged it “the most paltry village … a desolate picture…. The whole aspect is somber and wild and inspires a profound melancholy,” while a German explorer called it “savage … dismal and romantic” and rated it “one of the most unhealthy places of the New Continent…. The unfortunate inhabitants breathe a burning air, full of insects.” Then, in the middle of the twentieth century, it briefly became a playground of the jet set.

The site took its name — Acapulco — from a Nahuatl phrase thought to mean “place of broken reeds,” but to Spanish ears it sounded like “agua pulcra” — clean water — and this seemed to make sense because of the bay’s great depths. But after a night of hard drinking it probably sounded more like “agua pulque,” or pulque water. Pulque is an alcoholic drink made from the fermented sap of the maguey plant. Popular in Mexico at least since Aztec times, it is thick, opaque, and slightly foamy, like the waters of the bay, or the drinkers’ tongues and brains. But whatever you called it, this forlorn spot was one of the most important places in the world. Through it passed much of the world’s silver, the default currency of the new global economy.

Promotional poster for the film Fun in Acapulco, 1963.

The 1963 movie starring Elvis Presley and Ursula Andress promoted Acapulco’s mid-twentieth-century reputation as a swinging destination. Today the city is known in Mexico as a weekend getaway for residents of the capital. Internationally, it is best known for spring break excesses and drug war violence.

Elvis, playing a lifeguard and hotel singer, performs such unforgettable songs as Margarita, The Bullfighter Was a Lady, and the incomparable No Room to Rhumba in a Sports Car. Elvis’s scenes were shot on a Hollywood lot. He never visited Acapulco.

In January 1616 the China Road was flooded with thousands of travelers of every description, all on their way to the bay. Among them were government officials, wealthy gentry or their representatives, soldiers, miners, friars, merchants, peddlers, craftsmen, sailors, adventurers, caulkers, carpenters, blacksmiths, sail makers, porters, gold panners, gamblers, prostitutes, beggars, healers and herbalists, fortune tellers, actors, clowns, and cutpurses.

Caravans of mules were prodded forward by professional muleteers and their assistants and slaves.

A Dutch engineer named Adrian Boot would likely have been among the throngs descending the China Road. As he wound his way down to the bay the engineer observed the progress on the fortress that he had recently designed, called the Castilo San Diego de Acapulco, now under hurried construction. Beyond the fort, and the town it overlooked, he saw resting in the harbor two enormous galleons, each weighing in at between a thousand and two thousand tons (a law limiting their size to three hundred tons was routinely ignored). The residents of New Spain called these the naos de China, the China ships. They were the richest vessels in the world, and their presence would transform the town. The giant ships had set sail from Manila, nine thousand miles away (and substantially farther by the routes they had taken), half a year before, in the summer of 1615, taking advantage of that season’s monsoon winds. Happily, each had arrived safely in Acapulco, one on Christmas Eve, the other on January 1.

It was never an easy journey. While the westward voyage was a not-too-hazardous straight shot lasting about four months, the return trip was much longer — sometimes taking as many as nine months — and considerably more difficult. To catch favorable winds the galleons would first sail north, in the early years sometimes stopping in Japan, and then cross at a latitude of about 40 degrees — about as far north as New York City. Had they continued on that course they would have reached land near the present Eureka, California, but since some early galleons had been wrecked off Cape Mendocino they instead angled south as soon as they saw seaweed, shorebirds, and other indications of approaching landfall. The galleon voyages continued regularly for 250 years, from the first crossing in 1565 until 1815, when the Mexican War of Independence brought them to an end; yet, because of their far northern route, the ships never discovered the Hawaiian islands, which would have made a most welcome midway resting point.

Even leaving aside the arribadas — ships that were forced to return to port (all four of the ships departing Manila in 1616 and 1617 would fall into this category) — and other ships that were destroyed by storms or simply vanished (in the first decade of the 1600s six galleons were lost), the trip was perilous. The voyage was “the longest and most dreadful of any in the world,” a seventeenth-century traveler wrote without exaggeration, “as well because of the vast ocean to be crossed, being about one half of the terraqueous globe, with the wind always ahead, as for the terrible tempests that happen there, one upon the back of another, and for the desperate diseases that seize people in seven or eight months, lying sometimes near the line of the equator, sometimes cold, sometimes temperate, and sometimes hot, enough to destroy a man of steel, much less flesh and blood.”

Scurvy was always a problem on the eastward trips, and thousands of sailors and passengers perished during the journey over the long history of the voyages. “When it returns from that climate,” gloated a French buccaneer, “all the crew are so sick and moribund, that of four hundred men who may compose it not a quarter are in condition to defend her, for the malady known as scurvy never fails on the way from the Philippines.” (The Frenchman never took one of the huge, heavily armed ships, however; nor did anyone else except the English, who captured four, in 1585, 1709, 1743, and 1762.) Eighty people perished on a 1606 voyage, ninety-nine in 1620, one hundred five in 1629, one hundred fourteen in 1643. Around midcentury a ghost galleon was discovered drifting near Acapulco on which every person on board lay dead.

Those voyagers who survived the trip found it anything but pleasant. An Italian who made the crossing toward the end of the century reported that “there is hunger, thirst, sickness, cold, continual wakefulness, and other sufferings; besides the terrible shocks from side to side, caused by the furious beating of the waves … the ship swarms with little vermin the Spaniards call gorgojos [weevils], bred in the biscuit; so swift that in a short time they not only run over cabins, beds, and the very dishes the men eat on, but insensibly fasten upon the body…. There are several other sorts of vermin of sundry colors, that suck the blood. A multitude of flies fall into the dishes of broth, in which there also swim worms of several sorts…. On fish days the common diet was old rank fish boiled in fair water and salt; at noon we had mangos, something like kidney beans, in which there were so many maggots, that they swam at top of the broth, and the quantity was so great, that besides the loathing they caused, I doubted whether the dinner was fish or flesh.”

Small wonder that when the first signs of land were spotted the ships often erupted in a saturnalia called the fiesta de las señas, the festival of the signs. A law requiring such festivities to be kept within the bounds of “decency and modesty” must have been difficult to enforce. For the occasion the seamen, “clad after a ridiculous manner,” formed a mock court and sentenced the officers and passengers for all manner of transgressions. The thought of land cast away much of the gloom, despite everyone’s weakened state.

As a galleon followed the coastline south it would eventually be spotted from land. Often the first sighting would occur off Baja California. Messengers in small swift boats would spread the word, which would be taken up by horsemen and long-distance runners, so that by the time the galleon pulled into the bay it seemed the whole world knew of its arrival. It would not be long before it would be joined at harbor by smaller trade ships that had made the trip up the coast from Peru, along with a few from Central America and Chile.

On the approach of the galleon an escort boat was sent out to guide the big ship into the bay. The escort was charged with preventing any contact with the galleon before it was turned over to court officials. This was the first of several steps intended to ensure that imperial regulations were observed and all taxes paid. The shipping industry was highly regulated. Acapulco had had an officially authorized monopoly on the trans-Pacific trade since 1579 — there was no other legal landing port anywhere in the Americas — and trade between Mexico and Peru was limited in an effort to keep it from cutting into the trans-Atlantic trade with Spain itself. But the elaborate regulations were to a large degree a universally agreed-upon fiction, and all parties routinely conspired on violations of many of them.

The official bills of lading typically omitted large portions of the ships’ cargoes. These might be offloaded up the coast before the ships reached Acapulco, or the arrival might be arranged at nightfall, when the ships were not allowed to enter the bay. Then the contraband goods would be lowered over the side during the night onto boats waiting to receive them.

Arrival into the bay itself would be celebrated with a firing of all of the galleon’s guns. Before anyone could disembark, the keeper of the fort and the treasury officials would come aboard for an inspection. It was understood by everyone that the inspection would consist of accepting the sworn statements of the shippers as accurate without actually checking the cargo. In 1636 one inspector violated this understanding and opened some packages to determine their contents, thereby becoming the most hated figure in the history of the galleons — in response a new decree was quickly made prohibiting officials from “any innovation in the opening of packages.”

When the statements were accepted by the inspector they were sent by couriers to the capital, where the duties for the cargo were calculated and then conveyed back to the coast to be applied. By traveling around the clock the couriers could make the trip in three or four days each way. At this point, notes William Lytle Schurz, whose book The Manila Galleon (published in 1939 and now unfortunately out of print) is still the foremost reference on the galleon trade, “when the letter of the law had been complied with in this fashion and health drunk all around, both parties proceeded to the real business of the occasion — the making of arrangements for the landing of the illegal merchandise,” that is, such of it as hadn’t already been offloaded. Then, finally, the sick were transported to the hospital and the comparatively healthy to the church to give thanks for their good fortune. The cargo was taken to secured warehouse

s to await the opening of the fair, although if not enough palms were greased an unfortunate shipper might find his merchandise seized, removed to the royal warehouse, and sold off to enrich the king’s accounts.

Despite the hellish conditions of the voyage, in a few months many of the sailors would be back. The westward-bound ships usually departed between late February and the end of April. “Notwithstanding the dreadful suffering in this prodigious voyage,” one traveler reported, “the desire of gain prevails upon many to do it four, six, or even ten times. The sailors, though they foreswear the voyage when out at sea, yet when they come to Acapulco, for the love of 275 pesos, never remember past sufferings, like women after their labor.”

As the engineer Adrian Boot made his way down the China Road to the bay he could make out a multitude of creatures moving around like bugs over the burning sands — on closer view these would reveal themselves to be visitors to the Acapulco Fair, which despite the wretchedness of the town and the grimness of the Pacific crossing was one of the most famous and liveliest in the world. They were a diverse group, bedecked in all the costumes of the globe. They came from inland Mexico, from Peru, from the shores of the Caribbean, from Europe, Asia, and the far-flung world. They would swell the town to five times its normal population. Unfortunately, there was not a single hotel or inn in the town until 1698, so everyone vied for the right to a corner in the few available hovels; for the majority the beach would serve as home for the duration of their visit. Food, drink, and hospitality in Acapulco were notorious for high prices and low quality.

1616

1616