- Home

- Christensen, Thomas

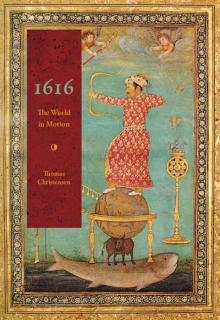

1616 Page 7

1616 Read online

Page 7

A recluse in the inner palace of the Forbidden City, the Wanli emperor must have had difficulty understanding the contentions of his empire and its borderlands. There China continued to dip into its enormous reserves of high-quality silk to make gifts to troublesome kingdoms, buying in this manner a momentary peace. Other powers also used silks as a component of their foreign policies. By 1616 Persia had become China’s most formidable competitor. (The Ottomans produced silk to a lesser degree within the Topkapi Palace complex in Istanbul, where unwanted princes were strangled with silk cords.) The Persian trade was promoted by Shah Abbas, who recruited Armenian merchants to sell silk goods. A fine collection of Persian silk textiles in the Kremlin is a result of trade exchanges with the Muscovites.

Around the beginning of the seventeenth century, silk workers in the new Persian capital of Isfahan developed a style of carpet in which silver threads were brocaded in a rich silk pile. These carpets — called “Polonaise” because some, made for recipients in Poland, contain Polish coats of arms within the design — do not seem to have been intended for the commercial market but were designated from the outset as elite diplomatic gifts; such gifts did, however, attract merchants to Persia where they then traded for other luxury items. The Polonaise carpets’ complex patterns, rendered in pastel colors (probably originally a result of the silks not taking dye in the same way as wools), appealed to European Baroque tastes.

Plan of Macau by Barreto de Resende, from Antonio Bocarro, Book of East India Fortresses, 1635. Public Library of Évora.

The Portuguese settlement at Macau was the only European post authorized by the Chinese on their mainland. It was an essential link in the Portuguese trade network that also included Melaka in Malaysia and Goa in India. In the seventeenth century Macau’s importance would diminish as a result of the loss of the Japan trade after the closing of that country to outsiders and the loss of the trade link with Melaka after its conquest by the Dutch in 1641.

More and more, however, the ancient land routes were being supplanted by sea trade. In China such trade had surged during the Tang dynasty (618–906), when Chinese traders carried silks from ports on the southeast coast of China to Vietnam, India, and other locations in South and Southeast Asia. From there they were sometimes transferred to ships bound for the west. Yet by the middle of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) China had become at best a reluctant participant in the competition on the seas.

The founder of the dynasty had already voiced doubts about the value of overseas trade in the fourteenth century. Confident that China — the “Middle Kingdom”— was central to all matters of importance, he had declared that “overseas foreign countries are separated from us by mountains and seas, and are far away in the corners of the world. Their lands do not produce enough for us to maintain them, and their people would not usefully serve us if we annexed them.”

Still, by the fourteenth century China could not resist experimenting in sea travel — in a big way. But the ambitious project backfired, putting an end to the country’s maritime ambitions for centuries. The emperor had decided to send out large fleets under the command of the eunuch Zheng He, a Muslim who had been captured in southwest China near Burma and castrated at the age of eleven.

Zheng’s voyages were the greatest maritime explorations in history to that time. One expedition comprised 62 large vessels and 255 smaller ones, manned by 27,870 men, mostly from Fujian province; there were six voyages in all. The largest vessels were said to be 444 by 186 feet — bigger (by far) than a football field. Perhaps because of his background and religious affiliation, Zheng tended to follow established Muslim trade routes. The fleet sailed to Southeast Asia, India, Persia, and the east coast of Africa. Its ships carried vast quantities of silks, along with porcelains and other luxury items, which were exchanged for spices, gemstones, and exotic animals such as ostriches, rhinoceroses, giraffes, and lions for the emperor’s amusement. But to the Chinese this was not a trade mission. The Ming government prohibited, or severely limited, foreign trade. To get around this, everyone agreed that any goods exchanged were to be viewed as diplomatic gifts and the goods received as tribute. Such tribute helped to reaffirm the mandate of heaven by which authority the emperor ruled the world.

But the emperor had overextended the country. The sea voyages — expensive undertakings, lacking a clear purpose — were not sustainable. China needed to devote resources to confronting the threat on its eastern border from the Mongols, led until 1405 by Tamerlane, whose legacy would include the Mughal empire in India; it was also recovering from an expensive failed attempt to conquer Vietnam, and continuing to devote resources to finishing the Great Wall. The treasure fleets were seen as a frivolous expense. Zheng He’s ships were disposed of and his records and maritime charts burned to ensure that no recurrence of such follies would ever occur. Shipbuilding was banned. It was the beginning of the drawing inward of Ming China, which would no longer be as forceful with outsiders as it once had been. The great ocean voyages became a dim memory, and the new European sea powers now patrolled the Asian seas China had once commanded.

By the time of the Wanli emperor the government had become so paralyzed that decisive action on the seas seemed inconceivable. The Forbidden City, from which the emperor ruled in the new capital of Beijing, had swollen into an enormous and unwieldy bureaucracy. It has been estimated that the city held around a million people and supported as many as sixty thousand imperial family members.

Despite the prohibition on trade, many Chinese longed for foreign goods and foreign markets. An illegal sea trade grew up that was centered in Fujiang province and the nearby island of Taiwan. Without effective policing by the government, fishermen there sometimes turned to smuggling, and smugglers sometimes turned to piracy, and pirates sometimes organized themselves into virtual navies. The widening gap between rich and poor during the later Ming helped drive farmers, laborers, and fishermen to desperate measures. Around the time the first galleons sailed to Acapulco, a pirate named Lin Feng (or Limahong) assembled a large fleet carrying more than a thousand men, with which he nearly captured Manila. Had he been successful it would have been a major setback for Spain’s efforts to maintain a foothold in Asia. Chinese and Spanish forces joined together against the pirate band, but the Spaniards’ stock fell in the Chinese estimation when it came out that they had trapped Lin Feng but carelessly allowed him to escape. This was a blow to Spain’s hopes to be granted a post on the Chinese mainland.

The Portuguese had got there first. They discovered that trade restrictions were not being enforced in Canton. They were allowed to establish a trading post in Macau, which grew into a walled city that was an important link in Portugal’s Asian trade network. (The walls were a mixed blessing: they provided defense but also cut off the colony from the rest of the mainland, rendering it dependent on China for its subsistence; Portuguese were not allowed to pass beyond the walls into the interior.) From Macau the Portugues acted as middlemen, facilitating an exchange of silver and silk between the hostile powers of Japan and China. This situation was complicated when the Dutch entered the arena around the beginning of the seventeenth century, insisting as ever on open trade as a basic right (except for goods on which they claimed a monopoly), to be secured with force if necessary. They made an even more unfavorable impression than the Spaniards had on the Chinese, who regarded trade as an embarrassing secret. China was insistent about keeping the Dutch “red-haired barbarians” out of Canton Bay, labeling them “people with filthy hearts.” Consequently the Dutch hovered ominously around the island of Taiwan, where they mingled with the pirates who had holed up there. They spent the next few decades trying, without a great deal of success, to break into the China trade. At one point they even attempted to organize a multinational pirate armada to attack China and force the trade concessions they were after. These wild ambitions were frustrated, but by the mid-seventeenth century they would succeed in winning some grudging concessions.

Among Chinese merchants and worker

s imperial restrictions and taxes were increasingly resented, and some of the pirates were viewed as Robin Hood–like figures. A colorful Taiwan-based pirate known as Yan Siqi was a subject of legend, together with his sidekicks the strongman Iron Zhanghong and the clever and resourceful Deep Mountain Monkey. In addition to the Chinese pirates, seafaring Japanese freebooters were supported by daimyo (regional warlords) who resented the shutdown of Chinese markets. Japanese pirates made daring raids not just on shipping but on the mainland as well, and they sometimes collaborated with Chinese or other renegades.

Early in the Wanli emperor’s reign China had relaxed its restrictions on trade, but it had excepted Japan. The restrictions proved difficult to enforce, as it was hard to secure thousands of miles of coastline without a navy. An illegal trade in silk and silver that was a precursor to the Manila–Acapulco trade flourished between the two countries. But as hostilities became more overt and the East Asian powers went to war in the 1590s this illegal trade became increasingly difficult to maintain without the aid of Portuguese intermediaries. This was some of the action the Spanish, latecomers to the arena, tried to muscle in on by way of Manila.

On their westward route to Manila, the galleons sometimes paused at Guam in the Mariana Islands. The Spaniards called that archipelago the Islas de los Ladrones, or Islands of the Thieves — the Ladrones for short. The name expressed the first of many cultural misunderstandings that would result from the European entry into the Pacific.

The Portuguese navigator Magellan, in command of an international crew in the service of Spain, had made the first European landfall in Asia by way of the Pacific in March 1521. Spain had been unable to reach Asia by the eastward route around Africa because of Portugal’s prior claim and established presence. So it was forced to sail west. As the Spanish ships had drawn in to the island of Guam, native people swarmed around them in proas, or small outrigger canoes. Audaciously, they clambered onto the big ships and, before the sailors’ eyes, helped themselves to anything that wasn’t nailed down. The sailors, enfeebled by scurvy, barely managed to drive them off with crossbows. Less than two months later Magellan would die in a similar clash in the Philippines.

The natives of the Marianas Islands were communal people who did not have the same concept of private property as the Europeans. Again and again the Spanish would be perplexed and frustrated by the way the people of the Marianas seemed to simultaneously engage in friendly trade and violent warfare — they seem never to have realized they were dealing with multiple clans, each with its own sense of relations with the intruders. As a result of these early encounters, the islands would continue to be known as the Ladrones for more than three centuries.

Rua Direita, Goa, 1596, engraving after a drawing by Jan Huygen Van Linschoten, from his book Travel account of the voyage of the sailor Jan Huyghen van Linschoten to the Portuguese East India 1579–1592.

The Dutch merchant van Linschoten (1562–1611) lived in Goa between 1583 and 1588 as secretary to the Portuguese archbishop there. On his return to Europe in 1592 he collaborated with the scholar Bernardus Paludanus (Berent ten Broecke) on books about his travels.

The Itinerario was the most popular of his books; it was frequently reissued and translated during the early seventeenth century. It describes all of maritime Asia from Mozambique to Japan. This engraving shows the Rue Direita (“straight street”), the main drag of Goa. Located on the central western coast of India, the city was notorious among Europeans for its hot and humid climate and its summer monsoon rains.

The handful of Magellan’s crew who made it back to Europe achieved the first circumnavigation of the globe, and their cargo of thirty tons of cloves and other spices proved valuable enough that both Spain and Portugal immediately made plans for new expeditions in search of more spices. After Columbus’s first voyage, Pope Alexander VI had drawn a vertical line across the globe establishing the separate domains available to the Spanish and Portuguese for new territorial claims. Soon the two powers quarreled over rights to the “Spice Islands,” normally understood to refer to the part of the Southeast Asian archipelago known as the Moluccas but sometimes used in a broader sense to refer to spice-producing regions of the South Pacific and Southeast Asia generally.

It was not clear to anyone where the line would continue on the far side of a globe whose expanse was only beginning to be known, particularly since there was no reliable way at that time of measuring longitude. Spanish maps conveniently exaggerated the size of Asia, moving the islands east into their domain. In 1529, a few years after Magellan’s ships had arrived home, the two powers negotiated a treaty that redrew the line. Spain ceded its claim to the Spice Islands but retained rights to the Philippines, while in the Atlantic the treaty gave Portugal a large part of Brazil. The division continued to be observed, for the most part, even during the uneasy merger of Spain and Portugal from 1580 to 1640.

Because of the preexisting relations between the Chinese and Portuguese, Spain had little choice but to rely on Manila as its base of operations for the Asia trade. Having won the support of the Chinese, the Portuguese at Macau successfully turned back efforts by the Spanish in 1598 and the Dutch in 1601 to establish their own trade operations in the Canton region. Spain was unable to venture further west, because Portugal had secured important bases at Goa on the western coast of India and Melaka on the Malaysian peninsula.

The main hub of Portuguese undertakings in Asia was Goa. Portuguese activities there are well known, thanks to the work of its Chronicler and Keeper of the Archives from 1631 to 1643, Antonio Bocarro. Bocarro was a Portuguese Jew, born in 1594, who arrived in India in late 1615 or early 1616 and spent nearly a decade as a soldier in Cochin. His Decades XIII is a detailed account of Portuguese activities in India from 1612 through 1617. He was also the author of a helpful book with the formidable title of Book Containing Designs of All the Forts, Towns, And Settlements in the Oriental State of India along with Descriptions of Their Situation and of All They Contain, Such as Artillery, Garrisons, Population, Income and Expenditure, Depths of the Sea Approaches, Neighboring Princes in the Hinterland, Their Strength and Our Relations with Them, and Whatever Else That Is Subject to the Crown of Spain.

Bocarro describes a lively trade involving about a dozen main trade routes connected to Goa. Ships traveled back and forth to Lisbon, Mozambique and Mombassa in East Africa, Muscat and Basra on the Persian Gulf, Sind in current Pakistan and Diu in northern India, Kanara and Cochin in southwestern India, Celon, Manila and Macau, Malacca, and the Maldives and Laccadives off southern India. Bocarro notes, however, that by the time he arrived in Goa trade with Malacca and Manila had greatly declined, because Dutch boats lay in wait to attack ships traveling through the Straits of Singapore.

Antonio Bocarro might have been related to Gaspar Bocarro, whose story he tells in his Decades. In 1616 Gaspar Bocarro became the first European to reach Malawi, inland from Mozambique in Africa; it would be another 250 years before the Scottish explorer David Livingstone would reach the same region in a more famous journey. Bocarro made a difficult journey from Tete on the Zambesi River through the Shire Valley to Lake Chilwa near Lake Malawi, the great inland lake in central Africa, then through the south of Tanzania and back into Mozambique. The Portuguese wanted to slow the spread of Islam in eastern Africa; later they became engaged in gold trade in the region, which ultimately had the result of disrupting ancient eastern African trade networks. In exchange for beads and textiles they acquired ivory and took slaves to work on plantations in Mozambique and Brazil.

Manila, 1619, by Nicolaes van Geelkercken, engraving, from East and West Indian Mirror, combining accounts of the navigations of Joris van Spilbergen and Jacob le Maire.

Joris van Spilbergen’s fleet cruised around Manila Bay for about a month in early 1616, harassing shipping and generally creating havoc. He withdrew when the Spanish governor of Manila, Juan de Silva, put together a large armada with the plan of attacking the Dutch headquarters in Indonesia; a

fter de Silva’s death the expedition collapsed in failure.

Chinese traders were already active in the Philippines when Magellan made the first Western contact there. That trade was one incentive for the Spanish to conquer Manila in 1870. From that time on the Spanish presence in the Philippines was always precarious. While Jesuit proselytizers made good progress in converting peoples of the archipelago, Spanish settlers and traders failed to successfully colonize much of the islands and were largely restricted to the area around Manila, where they depended to some extent on the forbearance of powers such as China and Japan for their survival.

The Spanish colony in the Philippines was, technically, a viceroyalty of Mexico. In practice, because of their vast distance from both the Americas and Europe, the Philippines were mostly self-governing. Because the Spanish could not exercise control over all the islands of the Philippines (of which there are several dozen large ones and some seven thousand in all), and because they made little effort to exploit the natural resources of the region or to develop its agricultural potential, they were reduced to operating what was essentially a trading post. The economy of the Spanish Philippines was overwhelmingly dependent on the profits from the galleon trade. In the years when the galleons failed — both the ships that turned back and those that were lost were calamities for their investors — the small, fragile community was hard-pressed to survive.

While the China trade was always the most important, there was a good variety of products from different regions. A Jesuit historian wrote in the mid-1600s about the importance of Manila as a trading post:

Manila is the equal of any other emporium of our monarchy, for it is the center to which flow the riches of the Orient and the Occident, the silver of Peru and New Spain, the pearls and precious stones of India, the diamonds of Narsinga and Goa, the rubies, sapphires and topazes, and the cinnamon of Ceylon, the pepper of Sumatra and Java, the cloves, nutmegs and other spices of the Moluccas and Banda, the fine Persian silks and wool and carpets from Ormuz and Malabar, rich hangings and bed coverings of Bengal, fine camphor of Borneo, balsam and ivory of Abada and Cambodia, the civet of the Lequios, and from Great China silks of all kinds, raw and woven in velvets and figured damasks, taffetas and other cloths of every texture, design and colors, linens, and cotton mantles, gilt-decorated articles, embroideries and porcelains, and other riches and curiosities of great value and esteem, from Japan, amber, varicolored silks, escritoires, boxes and desks of precious woods, lacquered and with curious decorations, and very fine silverware.

1616

1616